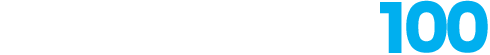

Today, we explore Johnny Cash’s 1994 comeback American Recordings.

When people ask where my grandpa is from, he doesn’t name a town. He says he was born “across the river from Johnny Cash.”

There’s only one story my grandpa ever tells about his childhood. It’s 1955, in Arkansas, and he’s standing on his motorcycle, prying a bathroom window off the wall with a pocket knife and a screwdriver. He never got more than a fifth-grade education, but he’s breaking into a high school. He’s doing this because “I ain’t paying no two dollars for a concert.” The concert? Elvis Presley and Johnny Cash. Elvis, he’s pretty good, my grandpa recalls. He’s alright except for the foolish hip movements. But Johnny, he’s got presence.

He was there from day one, from the first day “Cry, Cry, Cry” got played on the radio. He bought every record. He knew every producer Johnny ever worked with, every sideman he ever played with, every man down and woman gone. He saw in Johnny not just the Southern man to emulate, but something close to a holy figure. Johnny Cash was the only infallible man on earth. Until 1994.

The popular story goes like this: It’s 1994 and Johnny Cash’s career is all but dead. It’s a ghost haunting Billy Graham crusades and the dinner theaters of Branson, Missouri. He spent the 1980s a lost soul, recording bad music (“The Chicken in Black”) and watching the embers of his career fly away into the night. But then Rick Rubin, a bearded and inscrutable mystic, a man known for producing hard rock and hip-hop, brings him back to life in a house overlooking the Sunset Strip in West Hollywood, California with a brilliant idea that no one had ever thought of before—put Johnny Cash in a living room, hand him a guitar, set up a microphone, ask him to play the songs he loves, not for anybody else, just for him.

Cash’s face lights up. He sings gutbucket songs about sin and redemption, and in the blink of an eye, Johnny Cash is himself again. He snaps out of his coma. He makes American Recordings, and all the critics love it. Hell, everybody loves it. He’s playing South by Southwest and Glastonbury and he’s on the road to becoming an eternal symbol of punk rock and anything that’s real, man, you know, authentic. Rubin is a miracle worker and he encourages Johnny Cash to make the best music of his life. This is the door Johnny Cash walks through to dethrone Hank Williams as the king of country music.

But the true story of American Recordings is messier than that. It’s true that Johnny Cash had it rough in the ’80s. Columbia didn’t know what to do with a legacy act from 1955 and reluctantly dropped him, then the label he went with afterward, Mercury, treated him like he didn’t exist. Nobody was hearing his albums. One possible reason is that the country music business in the ’80s was making some historically terrible shit because of Urban Cowboy, a John Travolta vehicle easily summarized as Saturday Night Fever in cowboy boots. For the first half of the decade, the prevailing style bent toward the slick, the saccharine, the easy-listening. This was an environment that had little room for Johnny Cash, who came from the pill-guzzling highway to hell that Sun Records paved.

But he had also been recording for decades, and his operating expenses were enormous. His distractibility was enormous. He was on and off pills, he had to play shows with the country supergroup the Highwaymen and he starred in a remake of the John Ford film Stagecoach and he was in his fifties and he had this thing going on with his jaw and, well, it happens.

Despite all this, and in defiance of conventional wisdom, his material in the ’80s wasn’t all bad. “The Chicken in Black” is the sound of a brain breaking, but if you dig a little, you find that he also sang songs by some of country and folk’s best songwriters, from Billy Joe Shaver to John Prine and Guy Clark. In 1983, one year after it came out, he covered Springsteen’s “Highway Patrolman,” one of the toughest Springsteen songs to cover because of its ambiguous morality. It became one of the most artistically successful and satisfying covers of Cash’s entire career.

More accurately, the problem with his ’80s work was the lack of a rudder. His shows weren’t great, he had gotten corny, and nobody in the business was really advocating for him. He needed somebody to say, “You’re great, and your best work is ahead of you.” A Rocky without a Mickey, he spent too much time looking at his rearview mirror.

Luckily, new people were taking notice of Cash in the ’80s. New scenes, far away from Nashville. Nick Cave covered him on two albums in ’85 and ’86. In ’88, a British punk tribute to Cash called ’Til Things Are Brighter was released. It featured Pete Shelley of the Buzzcocks, Marc Almond of Soft Cell, and Jon Langford of the Mekons. It caught the critical eye of NME and Cash loved it.

And in 1992, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, one of only a handful of country singers ever invited. And then in 1993, Bono asked him to record lead vocals for a song on the new U2 album. Fucking U2. Six-years-after-Joshua-Tree U2. And it wasn’t just any song, it was album closer “The Wanderer,” pure Johnny Cash fan fiction, a post-apocalyptic Christian epic that had only-Johnny-Cash-could-even-attempt-this lines like “I went out walking with a Bible and a gun.”

A Johnny Cash comeback felt like a very real possibility. One problem. Branson. Poor Johnny got entangled in a deal to build a $35 million tourist trap in Branson called “Cash Country” and a theater with his name on it that would be his home base for live shows. The deal went bust, construction problems, new investors came in, and it became the Wayne Newton Theatre. Cash still had to play a bunch of dates there even though he was off the project. He had no choice. The money was too good.

All this is in the back of his head when he plays the Rhythm Café in Santa Ana, California in February ’93, the last show before he heads back to Missouri. He can hear Branson, and it’s the sound of wolves. There’s only one relief, and it’s that Rick Rubin, Def Jam co-founder, producer of the Beastie Boys and Public Enemy, wants to meet him after the show to make an album.

Cash is listening. He thinks Rubin wears clothes that “would have done a wino proud,” but he likes his individualism, and he knows that his own back is against the wall. So he goes to the hills above the Sunset Strip. He sits down in Rubin’s living room and plays songs that mean something to him, just him and his guitar, and Rubin rolls the tape. In three days, they’ve got north of 30 songs. Cowboy songs, folk songs, and old songs figure heavily. You know, songs about God, murder, trains, and everything else that makes America.

Some of these songs are originals that Cash has been protecting from the black hole down which Mercury sent his music. These lock-and-key songs are the best. “Drive On” is a look at the inhumanity of Vietnam, about the soldiers who see their buddies die and have to walk on anyway. The strong vocal performance and catchy melody sound subversive in a way Cash hadn’t in a long time, as though they’re covering up brutality and PTSD. “Like a Soldier,” a song about a man trying to find salvation and forgiveness after a hard journey and a lot of mistakes, has beautiful lyrics Cash was wise to hide from Mercury.

There are faces that come to me

In my darkest secret memory

Faces that I wish would not come back at all.

Rubin’s excited by all this, but he’s still looking for the Johnny Cash who committed a murder in Nevada just to see the life drain from an innocent man’s eyes. When Cash plays an updated version of the murder ballad “Delia’s Gone,” he finds him. It’s based on an old folk song, he’d recorded it before, but there’s new life in it now. The protagonist is not terribly penitent, and he describes his crime in vivid detail, how much he hated Delia, how he tied her up and grabbed his “sub-mo-sheen.” It’s a murder ballad where the sinner finds pleasure in his sin. It’s Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison, not Johnny Cash at a Billy Graham crusade.

It’s a huge breakthrough, but Cash can’t stay because he has to do 40 dates at the Wayne Newton Theatre. Not even Edward Hopper could capture the alienation of Johnny Cash at seeing the buses of tourists and retirees showing up strictly for photo opportunities and trinkets, all while having to weather half-empty matinee shows and fight constant physical pain. This is the hell he’s trying to escape.

So when he comes back to L.A. in the summer of ’93, naturally he slams out two dozen more songs in a few days, because no way in hell is he going back to Branson. He does Leonard Cohen’s “Bird on the Wire” and another Cash original, the salvation from the sin, “Redemption.” It’s a sanctified song about the power of the blood of Christ, and it grounds the album with an earnest devotion to God that every good Cash album needs. The story of sin cannot be told without the story of salvation.

You’d think this was conceived as an acoustic album, but after Cash finishes recording, Rubin experiments with adding instrumentation from Mike Campbell of the Heartbreakers and Flea and Chad Smith of the Chili Peppers. It doesn’t really take, and he decides he prefers the iconic idea of Johnny Cash alone with his guitar. He sends Cash off to the Viper Room to play an insanely exclusive solo show for approximately zero people who deserve to be there, gets a couple live cuts to finish off the sucker, and names the finished album after his own record label, American Recordings. Cash preferred Late and Alone. Too bad.

It doesn’t storm any charts after its release on April 26th, 1994, but Rolling Stone gives it five stars and raves about it. This is the mythic Johnny Cash, the tortured cowboy out on the prairie picking out “Oh Bury Me Not” in front of a campfire and seeing God on the horizon. Meanwhile, Nick Cave and U2 cohort Anton Corbijn makes a video for “Delia’s Gone” that gets actual MTV play. It stars Kate Moss and imagines Johnny Cash as Robert Mitchum in Night of the Hunter. You don’t need to see “LOVE” and “HATE” tattooed on his knuckles because you know it’s there.

While all this makes him seem cool, it doesn’t translate to sales. The album peaks at a humble No. 23 on the Billboard country charts, though it does reintroduce Johnny Cash to rock audiences, to people who may conceivably own a Nirvana album. And it works, and leads to better, and better-selling, music later.

Half the fun of American Recordings is knowing that it’s not the end of something, but the start of something. It sends him down a road that ends with him writing some of the best songs he’ll ever write and it nets him an immortality-cementing hit in 2002 with “Hurt.” Which, by the way, is unthinkable. To begin your career in 1955 and have a hit in 2002 is like starting out in 1971 and having a hit in 2018. Who the hell could even do that?

Well, Johnny Cash, but not Johnny Cash without Rick Rubin. The album is good, but more importantly, it’s a shrewd marketing idea. The triumphant rebirth of the man in black, a tortured soul who sings about killing and being forgiven for killing. It’s showbizzy, of course. No man can be as “authentic” as Johnny Cash without a pretty firm grasp of how to work his audience. He had to stare at the grimy lights of the Sunset Strip to be the ancient voice of the dirt he’s known as now. A mythic American artist must be created and curated and rebranded, and Rick Rubin was in the right place at the right time to help Cash get there. And Cash knew he had a choice between giving this his best shot or withering in Branson. It’s hard to deny he chose wisely.

In hindsight, the album is not the unqualified success it was made out to be in 1994. I firmly believe people wanted Johnny Cash to come back so bad that they willed this album into being what they wanted it to be. While “Delia’s Gone” captures the sinful giddiness of “Cocaine Blues,” while his original compositions are truly great Johnny Cash songs, and while the general mood of a frontier campfire is cool and transportive, there are weaknesses.

There’s the Danzig song, “Thirteen,” the first of many gimmicky alt-rock collaborations Rubin would prod Cash into doing. The lyrics read like they were written in 20 minutes, which they were. And Cash has a booming, powerful voice but one thing he doesn’t have is a lot of vocal nuance. So when he tries out Loudon Wainwright III’s satiric “The Man Who Couldn’t Cry,” the smartassery those lyrics demand never shows up. And “Down There by the Train,” a beautiful Tom Waits composition written specifically for Cash, a Baptist epic of redemption where even John Wilkes Booth can feel God’s grace, doesn’t quite work either. Maybe because it’s too long. Maybe he could have sung it quieter. Maybe it needs an organ.

The album’s real overarching problem is having Johnny Cash play guitar by himself with no accompaniment. While the man did innovative things with the guitar (the paper trick is cool, come on) and kept good rhythm, the fact is that he couldn’t play. This is an acoustic guitar album with almost no acoustic guitar on it. It sounds a cappella in places if you’re not paying close enough attention. His vocal power has to carry him wherever he goes, and there are some songs where that’s just not possible.

It’s a problem Cash and Rubin eventually solved by recruiting the Heartbreakers to play on pretty much every subsequent song Cash recorded, to lend momentum, dramatic shading, and emphasis to prop up Cash’s delivery. This album has no such fix, so it occasionally drags when you divorce it from its story, that Johnny Cash is back. It’s good, but now that Cash is gone, it’s no starting place to understand his work. If you want to understand his appeal, there’s still only one definitive starting place, and that’s the prison albums, where country, gospel and rockabilly get soaked in ethanol.

My grandpa never bought a Johnny Cash album after American Recordings. He didn’t like this album because it was the first time he ever heard Johnny Cash sound weak, and he didn’t want to hear that. It was a Johnny Cash my grandpa didn’t want to know existed, a Johnny Cash who could die soon. It sounded to him like a man revealing himself too much, being too vulnerable.

That generational divide is important. I have problems with every Johnny Cash album Rick Rubin produced, though I like all of them. Rick Rubin is a savvy marketer and a sporadically excellent producer but his cover suggestions were never as smart as he thought they were, and I don’t think the world needed to hear Johnny Cash cover Depeche Mode. But that mistake is probably the reason we have “Hurt” and “The Man Comes Around,” Cash’s definitive song about God, so on balance I look the other way.

American Recordings is flawed, and it’s not a masterpiece. Nearly a quarter-century on, it’s just a good Johnny Cash album. But it brought him back to the ground, and that was necessary. He was no longer Johnny Cash, towering celebrity. He was Johnny Cash, human being. His vulnerability, his fallibility, was relatable. He didn’t sound perfect, but he sounded like himself again. And he was comfortable being himself again. There are two dogs on the album cover. He named them Sin and Redemption.